A Collection of Strange Gadgets: An Introduction to Lathouse

In a blink of History’s eyes, capitalist technology has seemingly invisibilized itself. Physical servers rooms with massive tape-drive storage and central terminals have given way to portable supercomputers that appear to function like magic. In reality, these devices are connected through a mass web of network connections underpinned by massive, environmentally devastating data centres and server farms. The extraction of raw materials that make up the components of these data centres, as well as the fuels needed to power them, further complicate this web.

And yet the AI bubble keeps growing larger and larger. The vast majority of working people are struggling under rising inflation, but usage of LLM services like OpenAI continues to rise drastically. AI psychosis from sycophantic LLMs designed to keep you asking questions and feel good using them is driving people not only to be hospitalized, but to disappear.

This abstraction away from the physical capital investments that make this technology work is key to the continued functioning of the current state of the global capitalist order – an order that continues to exploit and devastate the majority of the world’s population. Technology — at least how it’s viewed — needs to be turned back on its head. This is the driving idea behind Lathouse as a project.

The Lathouse

But what even is a “lathouse”? The lathouse is one of French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan’s more enigmatic terms. It appears very briefly in his Seminar XVII (The Other Side of Psychoanalysis) with little elaboration:

And these tiny objects — little a — that you will encounter when you leave, there on the footpath at the corner of every street, behind every window, in this abundance of these objects designed to be the cause of your desire, insofar as it is now science that governs it — think of them as lathouses.[1]

For Lacan, a lathouse is an object of capitalist science made to capture and siphon desire to the Other. It’s a little gadget, a gizmo, a technological marvel that dazzles. Lathouses aren’t just any random gizmos, however. As philosopher Isabel Millar states:

The crucial point Lacan was making was not just that these objects are causes of desire, but that they contain something of the voice. In that sense they are impossible objects that attempt to capture something of jouissance of the other’s body; in short communication devices, which allow the truth of our enjoyment to be recorded by the Other…[2]

In Lacan’s time, the most obvious example would’ve been a portable tape recorder (which some attendees of his seminar regularly used to records his lectures). Today, the obvious example (perhaps too obvious) is the smartphone — but we can think of any numerous tools like tablets, laptops, smartwatches…

The arrival and domination of lathouses as siphons of desire marks a change in the relationship between the subject and the Other — that is, the symbolic world the subject inhabits now that capitalist science has come to dominate it. Lacan calls this symbolic world — the language that both enables and restricts our socio-political interactions — the alethosphere:

In the alethosphere, the merger of the principles of reality and pleasure is coextensive with a merger of subject and Other. Patched into a surface network of social circuitry, the subject “interfaces” with the Other.[3]

As subjects, we use lathouses to patch into this sphere — they act like connecting cables that lets us access the truths of this sphere while they simultaneously

siphon our desire in order to keep the alethosphere running. Lathouses record our desire into the alethosphere, creating a strange hybrid world where individual desires are shared with the Other (and in turn, the social at large) without it feeling like we’ve shared those desires in a broader way. Interfacing with the Other in this way feels frictionless.

The collapsing of the pleasure and reality principles noted by philosopher Joan Copjec above was thought to be a new and powerful way for society to channel its desires into new truths and material developments. This new and powerful development would allow anyone reshape reality according to their most wild fantasies. No more need to indulge in desire through a retreat from reality — reality can be whatever we want it to be, if we put our energy and resources towards it.

This driving idea, of course, was more of a seductive, techno-utopian fantasy rather than what truly ended up happening:

The reality (of the market) principle was dearly calling the shots, telling the pleasure principle in what to invest and what pleasures ought to be sacrificed get the best returns on those investments.[3:1]

In reality, there was no beautiful merger — just a subordination of desire to the capitalist mode of production, the further integration of surplus desire into the reproduction of new commodities.

So it seems like we’re doomed — our desire is too enmeshed, too ensnared and subordinated to the desire of the capitalist mode of production, for us to combat it.

Maybe not quite. What’s key for Lacan in his conception of the lathouse is that lathouse are impossible objects. The lathouse is a particular form of the objet petit a, or object-cause of desire — emphasis on the cause, because the drives behind desire don’t really want to obtain the object, but rather circle around it endlessly. To actually capture the object would entail the end of the fantasy it structures — a devastation of the drive. We can thus say, a la French philosopher/psychoanalyst duo Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, that the lathouse works by breaking down:

Within the seemingly well-oiled, smooth-functioning alethosphere, the impossible, mythical objet petit a assumes the character of a malfunctioning, mechanical nuisance, a toy-like, mechanical thing that does not quite work.[4]

It’s this breaking down, this introduction of friction into a seemingly frictionless symbolic, that’s important. When the subject truly encounters the lathouse as lathouse — as that impossible object that structures a particular relationship to the symbolic, as an element of the Real — the illusion of seamless integration into the alethosphere is shaken:

Man, the prosthetic God of this alethosphere, is uprooted from every foundation, ungrounded, thus malleable or at one with the Other, but from time to time, and without warning, he encounters one of these lathouses, which provokes his anxiety. The chiasmic intertwining of man and Other, the absorption of the former in the latter, suddenly falters; man is pulled away, disengaged from his foundations; existence in the Other; he grows deaf or indifferent to the Other's appeal.[4:1]

That lingering sense of the Real, that thing which cannot be named, is what the lathouse can bring. It’s not something that can be easily fled through “disconnecting” — it’s something that shakes one to their core.

The Significance of the Lathouse

So that’s the lathouse. Why take this concept as inspiration for my work?

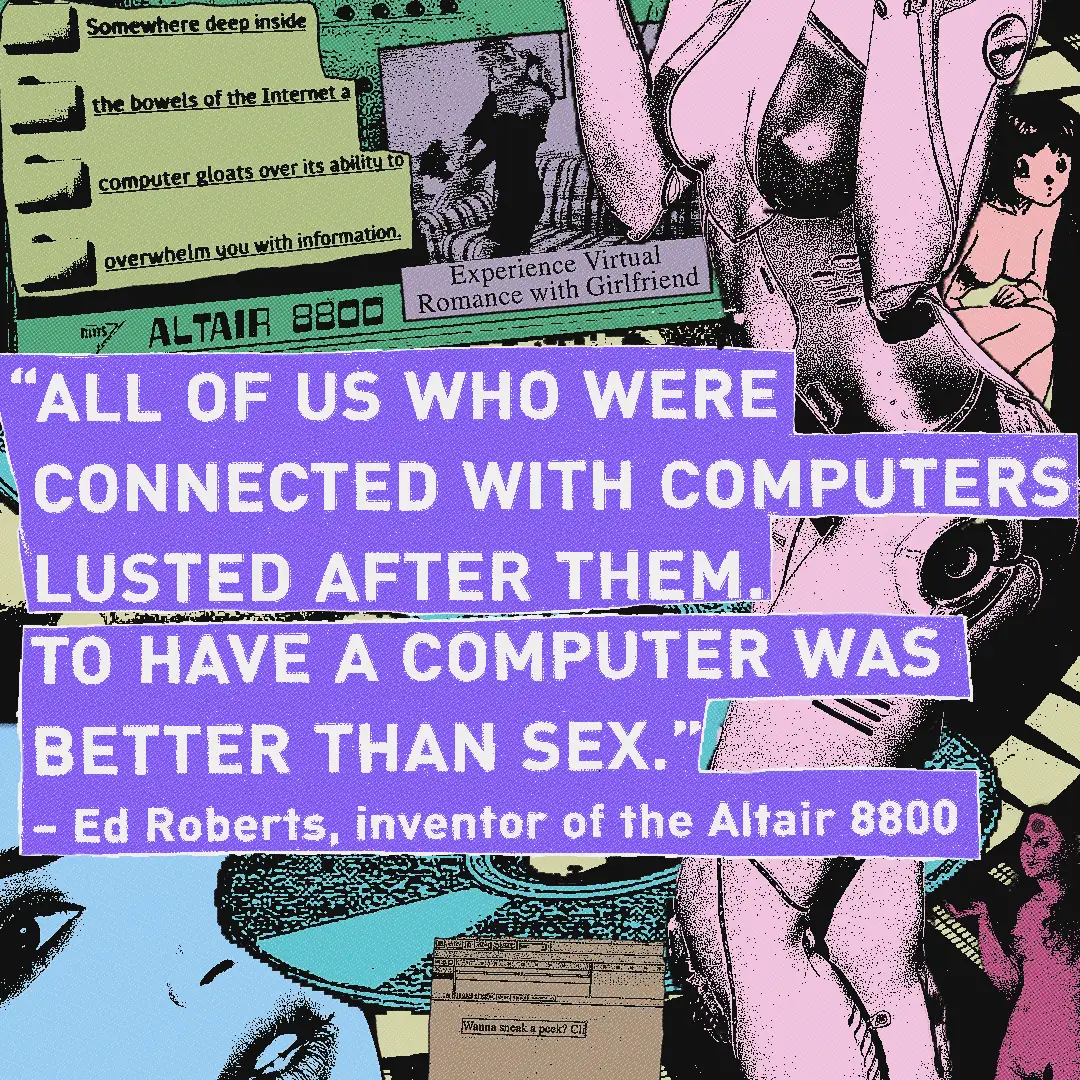

There is something interesting about the siphoning of enjoyment, of sexual desire, into this larger sphere of truth that lives “above” us (this is very Serial Experiments Lain). I want to explore this sexual desire, this sense of mastery and transcendence, that comes with the illusion of the “plugged-in nature” of today’s world. Why would someone say computers are better than sex, for example?

But to me, what’s most striking about lathouses is their ability to both seduce and shock. As mentioned, lathouses work by breaking down — their capacity to seduce one into a slipstream of smooth functioning is only possible given their status as objects of the Real. They are quilting points of desire, and when we break from the easy slipstream by sheer chance (among other things), we are brought back down to earth from the alethosphere, if just for a moment. When this happens, we re-encounter friction in the digital, a friction that must be channeled into a cognizance of gadgets like computers as tools.

They’re tools that aren’t just magical portals to a world of desire, but objects produced in a long chain of production, from the mining of raw materials, the extraction of energy resources to power data centers, and so on. This friction is critical to bringing attention to commodity fetishism as it operates in a world that’s about to be destroyed by an AI bubble.

And so I draw a lot of inspiration and imagery from earlier days in computational technology, where there was less abstraction and more friction in the use of said technology — even if that friction was still pretty much counterbalanced by a utopian sense of the collapsing of reality and pleasure principle together.

But my goal isn’t to blindly embrace the nostalgic of “retro tech” as a more natural, enlightened form of gadgetry. As the quote from Ed Roberts above shows, even gadgets we consider today to be rife with friction are still seductive, still siphons of desire. We can too easily slip into the illusion that “things used to be better” through the fetishization of friction. The truth of the matter is that this stuff was never natural — and the lathouse, as concept and as real-life gadget, is meant to expose that.

Future Blog Content

Future blog posts here will serve a couple of short-term and long-terms goals related to this project:

- A set of write-ups on the pieces that I’ve created so far, to help provide contextualize (maybe even historicize?) my work

- Long-form essays on themes linked to the project, like sex, technology, and capitalism

- Announcements for new works and pieces, some of which will be available at lathouse.studio

I hope you’re looking forward to encountering new collections of strange gadgets.

Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan Book XVII: The Other Side of Psychoanalysis, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. Russell Grigg (W.W. Norton & Company, 2007), 81. ↩︎

Isabel Millar, “Black Mirror: From Lacan's Lathouse to Miller's Speaking Body,” Psychoanalytische Perspectieven 36, no. 2 (2018): 6. ↩︎

Joan Copjec, “May ‘68: The Emotional Month,” in Lacan: The Silent Partners, ed. Slavoj Žižek (Verso, 2006): 95. ↩︎ ↩︎